How well do you know how a bicycle works? Many of you, myself included would have said “very well.” I learned to ride a bicycle as a toddler and, although I don’t ride frequently now, I’m very familiar with bicycles. Or I thought I was. I recently read an article that asked the following questions about bicycles to other people who reported to be familiar:

Could you draw one? Artistic skill aside, could you identify a picture of a functional bicycle against non-working photos?

The Science of Cycology: can you draw a bicycle?

40% of people in the survey made a fundamental mistake in drawing how a bicycle’s chain functions. This survey built on a 2002 study that found people rate themselves as having a far greater level of understanding of complex phenomena before being asked to describe its mechanics than they report after having to give a description. The study coined the phrase the illusion of explanatory depth.

The illusion of explanatory depth is phenomenon where individuals believe they understand the world with far greater detail than they actually do. The illusion of explanatory depth is not a function of blind overconfidence, or a person’s inability to admit ignorance; rather it is a function of a miscalibration of a person’s ability to understand and explain complex systems with detail. Because I interact with my refrigerator daily, and am familiar with what it does, I am pretty sure I know how it works. Or I have a pretty good idea, until I have to diagram or explain how it works.

Self-testing one’s knowledge of explanations is difficult. Testing knowledge of facts is easy. I either know that coriander and cilantro are the same plant or I don’t; it is much harder for me to challenge myself on what exactly coriander brings to a dish and how it changes the flavor of my food. Even when I am able to test myself, it’s harder for me to hold myself accountable; systems are harder to Google.

I recently had the opportunity to test my understanding of complex systems that I felt insatiately familiar with–my own cooking. I knew that I add oregano to my sauce when I make spaghetti, and cumin to a Middle Eastern inspired chicken dish. When I add these spices, am I adding them because I am looking to bolster or change a certain quality of the food, or because I know that the spices “belong” with the dish.

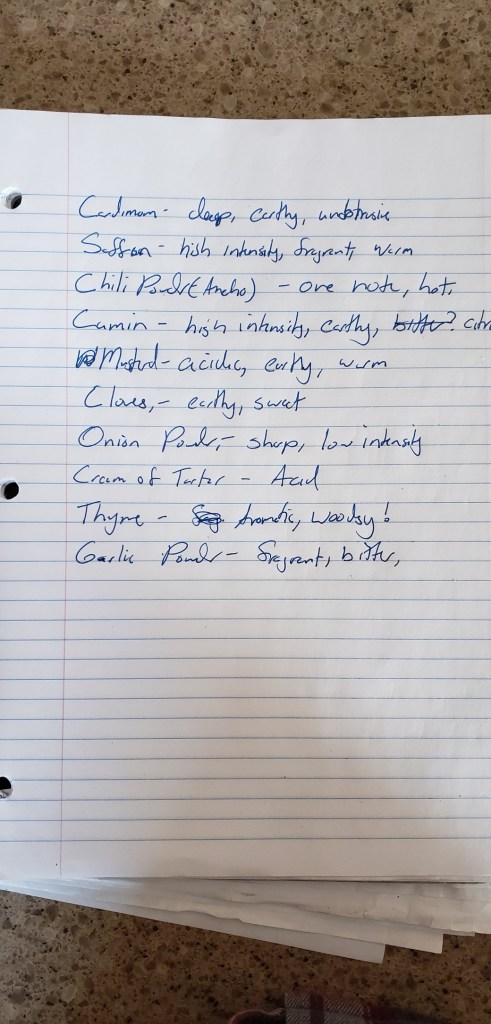

To test my knowledge of the spices in my kitchen I wrote down my impressions of each spice in my spice drawer:

I described no fewer than three spices as “warm and earthy.” How would one describe cinnamon? How does that description differ from turmeric? Allspice? How about garlic? Onion? I was amazed at how poorly I described spices that I used daily:

After a confidence-crushing attempt, I wanted to compare my pre-tasting notes with my experience tasting each spice individually. I set up a spice tasting:

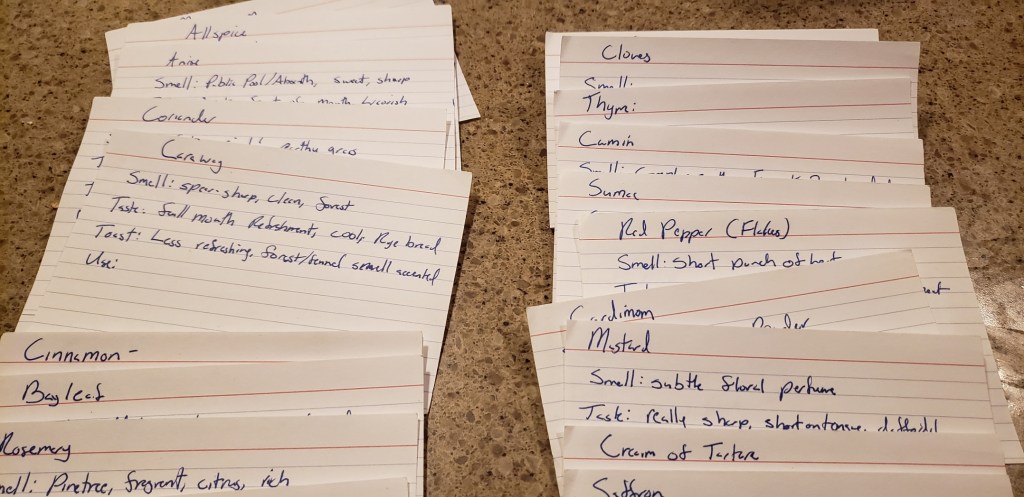

- First, I poured about a 1/4 teaspoon of a spice on to a plate and smelled it. I recorded my impressions on an index card.

- Second, I tasted the spice from the plate and wrote my impressions on the same index card.

- Third, I toasted the spice in a pan and noted how both the smell and flavor changed after toasting.

- Between each taste, I took a bite of an apple to cleanse my palate. Between each smell, I smelled a ramakin filled with coffee grounds.

I ended with a series of notecards (pictured below) that captured a much more accurate and personal description of the spice. During the tasting, I found that I was able to describe, with much more precision, flavors and smells that I was confident I knew prior.

Exploring my spice jar with intention was humbling and promises to be helpful in future food endeavors; but isn’t exactly profound. In his recent book, The Data Detective: Ten Easy Rules to Make Sense of Statistics, Tim Harford presents examples of how the illusion of explanatory depth heightens political polarization. Study respondents who had strong views on complex policies, such has cap-and-trade programs, were more willing to alter their views after being asked to describe the program. These study respondents realized, as I did about my own cooking, that they had miscalibrated how much they actually understood the mechanics of the programs they were previously passionate about.

Understanding how the illusion of explanatory depth impacts our worldview is helpful, but does not solve the problem that self-testing one’s knowledge of explanations is difficult. There is at least one tried-and-true method:

If you want to learn something, try teaching it.

Richard Feynman

The Feynman technique is a four step process to learning something. It can be applied to physical skills, fleshing out ideas, or confirming your reading of the daily news. The steps are as follows:

- Identify the subject

- Explain it to a child (or an imaginary child)

- When part of your description is missing detail or a link between information, study the gaps in your knowledge

- Simplify, fill the knowledge gaps, and explain again

The act of explaining concepts is a natural test to determine how well we understand the components of complex phenomena. Teaching disrupts the illusion of explanatory depth, because it requires explanatory depth.

How well do you know your bicycle, food, or passionate views?

Want to learn more about the idea of illusion of explanatory depth? Find more below:

- How to change your mind-Freakonomics (Podcast)

- The Data Detective: Ten Easy Rules to Make Sense of Statistics (Amazon Book Link)

- Related Podcast (Tim Harford)

- The misunderstood limits of folk science: an illusion of explanatory depth (study)